Screening billions of compounds in seconds with APEX

We're excited to introduce APEX (Approximate-but-Exhaustive search) [https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.24380], a novel search protocol designed to address the challenges of virtual screening in the era of ultra-large combinatorial synthesis libraries. In this post we’ll cover the motivation and underlying machinery behind APEX.

Virtual screening is a search problem

Combinatorial synthesis libraries (CSLs) like Enamine REAL have grown dramatically in recent years and offer access to billions or even trillions of make-on-demand compounds. While these libraries have the potential to greatly accelerate drug discovery, their size is a challenge for virtual screens, which use scoring functions like predicted binding affinity to evaluate molecules. For libraries numbering in the billions of molecules, these scoring functions are too computationally demanding to be run exhaustively on every compound. Furthermore, additional restrictions may be imposed during the screen to ensure molecules have favorable medicinal chemistry properties (a classic example being Lipinski’s “rule-of-5”). Virtual screening can be formulated as a search problem, where the goal is to return the best compounds that optimize the scoring function of interest (e.g., a docking score), subject to some constraints on molecular properties. Faced with the challenge of screening these ultra-large libraries, traditional screening algorithms may iteratively select a promising subset of molecules, often evaluating less than 1% of the total compounds in a library, which means that many potentially high-scoring molecules can be overlooked. APEX offers a significant departure from this approach; it leverages a machine-learned approximation to the scoring function that can be efficiently evaluated exhaustively on the entire library.

How does APEX work?

The APEX protocol consists of three main steps:

1. Train the surrogate

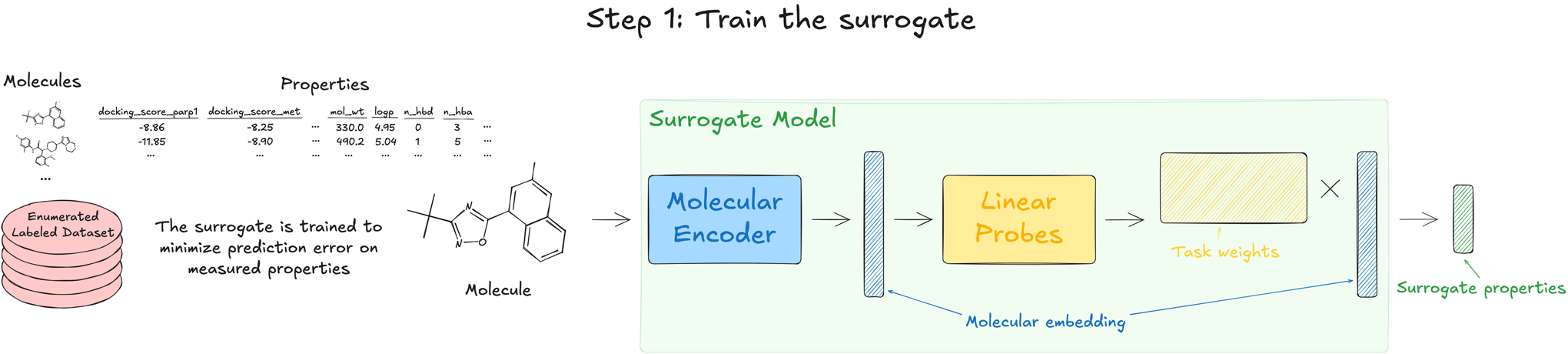

The starting point for APEX involves training a surrogate model to predict all relevant quantities, including the scoring objective of interest as well as the physiochemical properties used as constraints. This surrogate model is a multi-task neural network composed of two parts, an encoder that produces an embedding for each molecule, and a final linear layer that predicts each endpoint as a linear function of the molecular embedding. We use a message-passing neural network that operates on a 2D graph representation of the molecule, but other architectures could be used (e.g., a transformer operating on SMILES strings). This network is trained in a supervised manner to predict labels on an enumerated sample from the library (on the order of 1 million compounds). Though this surrogate model is faster than the original scoring function, it would still be impractical to evaluate billions of molecules for a routine search.

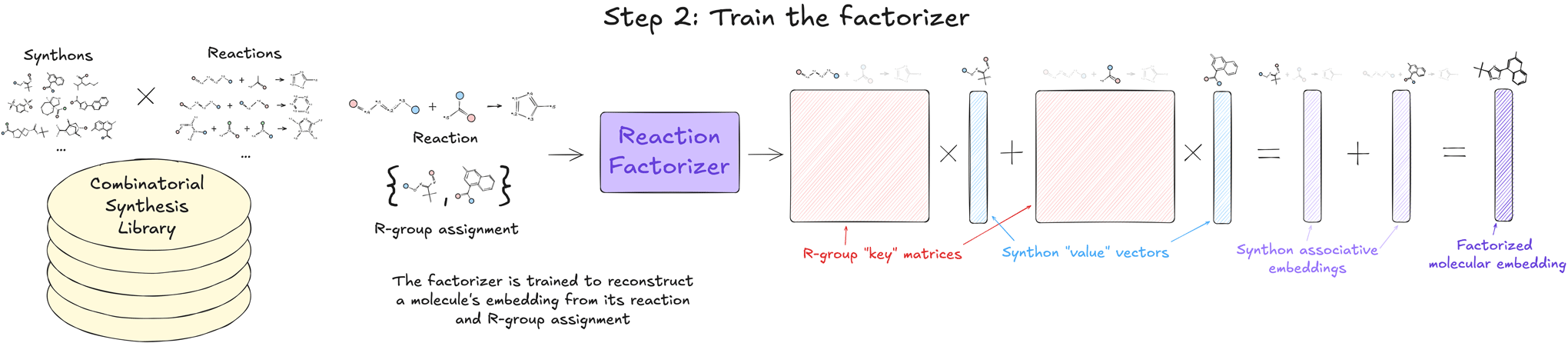

2. Train the factorizer

To make exhaustive screening efficient and practical, we exploit the inherent structure of CSLs to amortize much of the required computation. Each molecule in a CSL can be specified by the chemical reaction that produces it and the R-group assignment (i.e., which synthon occupies which numbered position in the reaction). We train a model called the factorizer to decompose the molecular embedding learned by the surrogate into a sum of matrix-vector products that correspond to the molecule’s reaction and Rgroup assignment. During training, the weights of the encoder are frozen, and the factorizer is trained to minimize the reconstruction error with respect to the original molecular embeddings.

This factorization is crucial because it allows us to express the approximate surrogate predictions as the sum of synthon associative contributions for each R-group assignment. These synthon associative contributions (which scale with the number of synthons and not the size of the library) can be pre-computed and cached for later use. This step effectively transfers the computational complexity of encoding the full library into the one-time cost of training the factorizer and then a small amount of precomputing and caching. Further, as new CSLs become available, the factorizer can either be applied out-of-the-box in a zero-shot manner to the new CSL or quickly finetuned on it so that the factorizer is better able to approximate molecular embeddings over the defined chemical space.

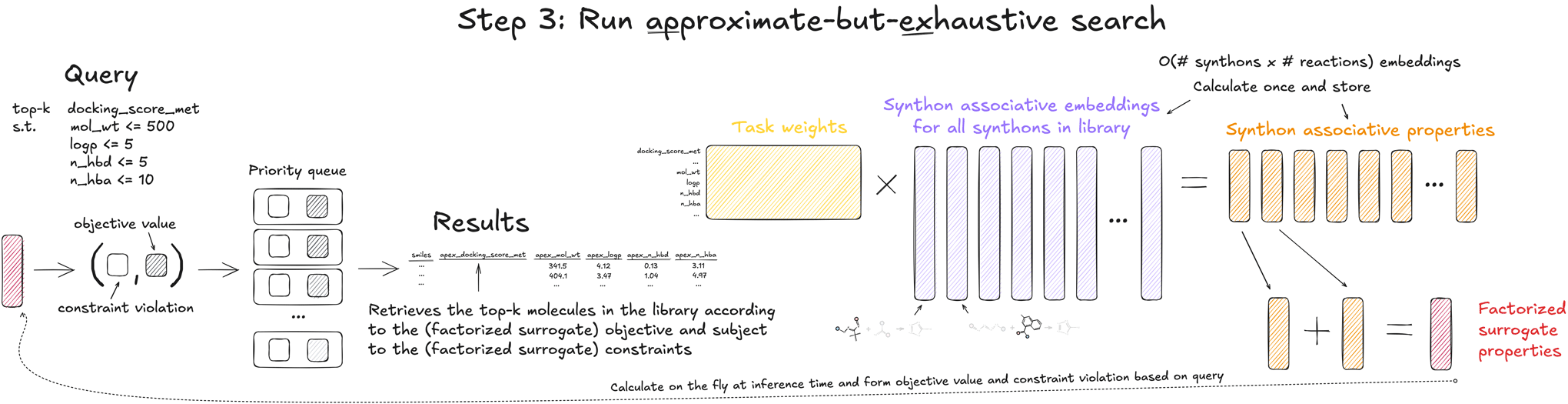

3. Run the search

Once the factorizer is trained and the synthon associative contributions have been cached, running a search over the library is incredibly fast. As part of the search, the user specifies the objective to optimize, the set of constraints, and the desired number of compounds to retrieve, k. Objective values and constraint violations are predicted on the fly as compounds are streamed into a priority queue, which retains the best k compounds. All intermediate computation and the top-k retrieval can be done directly on the GPU, which uses a custom accelerated priority queue developed in collaboration with NVIDIA. For a library of over 10 billion compounds, APEX can retrieve the (approximate) top 1 million compounds in under 30 seconds on a single NVIDIA Tesla T4 GPU.

Recall of top compounds under constraints

In our manuscript, we demonstrate APEX's capabilities on two benchmark CSLs that we constructed, containing over 10 million and 10 billion compounds, respectively. For the smaller library we fully enumerated it and calculated physiochemical properties and Vina docking scores against five diverse targets (PARP1, MET, DRD2, F10, and ESR1). Given that this library is fully annotated with scores and properties, we can evaluate the recall of APEX in finding the true top-k molecules, subject to different sets of constraints. Across all targets and constraints tested, APEX retrieves top-k sets at rates far exceeding picking compounds randomly. Though we can’t evaluate the true top-k recall for the larger library, the compounds retrieved by APEX from the 10 billion library showed clear enrichment of desirable docking scores compared to those retrieved from the smaller library, demonstrating the value of being able to screen truly ultra-large chemical spaces.

Unlocking chemical creativity

APEX is a significant step toward making exhaustive virtual screening a routine computational task. The ability to screen a CSL in excess of 10 billion compounds in under 30 seconds allows for efficient hypothesis testing and interactive exploration of chemical space. That could mean imposing tighter cutoffs on physiochemical properties to target the central nervous system or adding a constraint on an off-target’s score as part of a counter-screen. By enabling rapid, declarative queries that scale to ultra-large CSLs, APEX represents a powerful new tool for virtual screens.

Subscribe

Stay up to date on new blog posts.

Numerion Labs needs the contact information you provide to us to contact you about our products and services. You may unsubscribe from these communications at anytime. For information on how to unsubscribe, contact us..